In 2009, The Washington Post called Lane Stadium a “hostile environment for visiting teams.” It’s also up there on ESPN’s list of “Scariest Places to Play.” But when facing an athletic arch nemesis, a “scary,” “hostile environment” is exactly what a team hopes for. A stadium filled with tens of thousands of loyal fans, all moving together as one body, is perhaps the best weapon of all.

These days, a Virginia Tech football game is seamlessly scripted, with expertly produced video bits, impeccably timed chants and soul-shaking base. But there was a time before jumbotrons and jumbo turkey legs, when the scene was spontaneous and camaraderie a driving force.

“Back then, one of the things that made the atmosphere so different was we were more involved in it emotionally. Most of us knew players well. We were all part of the group. It was all part of what the tradition was. We were more connected,” Bert Kinzey recalls.

Kinzey attended games as a child in the 1950s and later as a student and member of the Corps of Cadets regimental band, the Highty-Tighties, from 1964 to 1968. Now he’s President Emeritus of the Highty-Tighty alumni and the award-winning group’s historian.

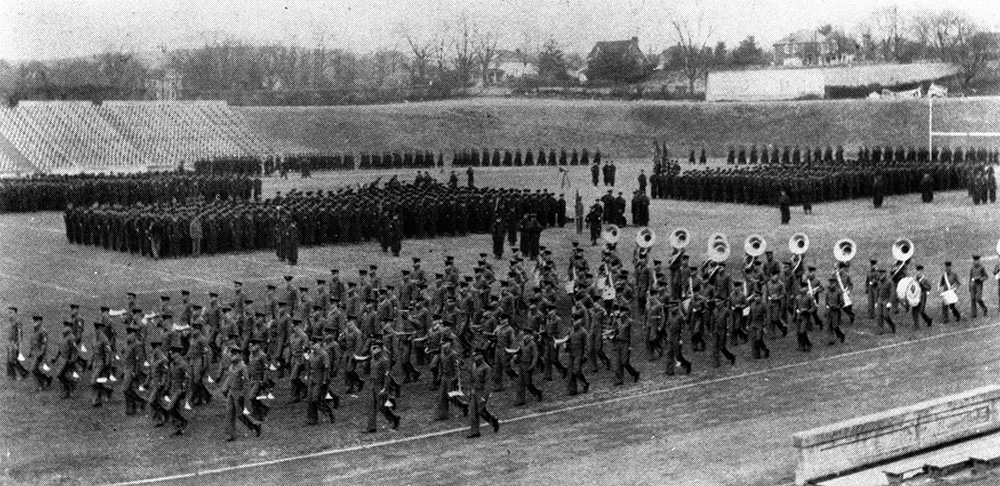

“The Corps was big back then. It was the dominant part of Tech, and they sat in a certain block in the stands,” Kinzey offers, who was a sophomore for Lane Stadium’s inaugural season.

While seated in the stands during games, the Corps would often perform hat tricks, or card tricks, using their white hats and navy-blue uniforms, or even orange and maroon cards, to spell out “VPI,” or “Go Tech, Go,” among other game day sentiments.

Another early tradition was the Highty-Tighties’ victory march, which was anything but militaristic. “Whenever we won, the band would go on the field and do a victory march. We became the antithesis of what we were. We turned our hats around backward, we played ‘Tech Triumph’ over and over again and went up and down the field to a wild drumbeat. The other students would pile in behind us.”

Skipper, the Corps of Cadets cannon, was born out of a fierce traditional rivalry, the VMI vs. VPI Military Classic of the South. After each win, VMI cadets would fire off their cannon, “Little John”, while taunting the Hokies with, “Where’s your cannon!?” Using Civil War era blueprints and scrap metal, Tech cadets got busy constructing their own artillery. The cannon was completed in the fated fall of 1963, thusly named “Skipper” in honor of President Kennedy’s naval background. Skipper still fires today when the football team enters the field and after every Hokie score.

The Marching Virginians, Virginia Tech’s first “all university” marching band, premiered in September of 1974. By the 1980s, the band had integrated musical traditions that we still know today, most notably the Hokie Pokie, which, until recently, was performed by the tuba section at the end of the third quarter.

And of course, there’s everyone’s favorite (and only?!?) turkey mascot, HokieBird, bench-pressing a large [imitation] dumbbell the number of times to match the score.

Former defensive coordinator Bud Foster’s iconic Lunch Pail Defense made its game-day debut during the 1995 season. Famously symbolizing a hard-working, blue-collar approach to football, the battered and well-used lunch pail now contains the names of the 32 Hokies who lost their lives on April 16, 2007. The tradition retired with Foster in 2019.

Bill McChain was the football public address announcer from 1998 to 2008, sealed in the history books for his distinctive rendition of “First Down! Hokies!”

“The traditions were cherished. We had a sense of duty and obligation. We felt like we were all part of it. It didn’t matter if you were a cadet or a civilian or faculty. We were all out there,” Kinzey concludes.

Traditions give fans infallible entertainment amidst a game of uncertainty. There is no way to know what a final score will be, despite all statistical predictions, but participating in customary game antics is tried-and-true. Traditions interlock players and fans alike, even as the seasons come and go, securing the message that we are all one big team. Perhaps it’s why “This is Home,” is such a poignantly accurate tagline.

And then, of course, there’s “Enter Sandman.”

“I will never forget when we played Notre Dame in Lane Stadium. When they played the song, the whole stadium shook and for the first and only time in my 20-year run as the PA announcer, I could feel the press box moving,” McChain adds.

Maybe it’s not the university’s most beloved tradition, but it’s certainly the most raucous, the one, for now, that makes our environment hostile, yet interconnected like family. How important it is that we can confidently jump up and down on such a solid foundation of time-tested fandom, else our legacy might fall into never, neverland.

Nancy S. Moseley is a freelance writer who, if she’s not actually at the game, opens all the windows in her home so she can hear Skipper fire.